Food waste accounts for ‘half’ of global food system emissions

Greenhouse gases resulting from rotted and otherwise wasted food accounts for around half of all global food system emissions, according to a new study.

Around one-third (pdf) of all food produced is either lost or wasted each year, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

One of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals is to halve global food waste and reduce food losses in production and supply by 2030.

The study assesses the emissions of food loss and waste along every link in the supply chain – from the time the food is harvested to when it ends up in landfill or compost.

It finds that, in 2017, global food waste resulted in 9.3bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent (GtCO2e) emissions – roughly the same as the total combined emissions of the US and the EU that same year.

Alongside the carbon emissions, this is occurring at a time when more than 800 million people were impacted by hunger in 2021, according to the UN.

The new study, published in Nature Food, also explores a number of ways in which the emissions from food waste can be reduced, such as halving meat consumption and composting instead of disposing waste through landfills.

Where food waste comes from

The global food system, from production through to consumption, emits around one-third of total annual greenhouse gas emissions – some 18GtCO2e. Food waste causes approximately half of this, the new study says.

Location, socioeconomic differences and other factors play a role in the emission levels of food waste around the world.

Developed countries, for example, generally have more advanced, more environmentally beneficial technologies – which can result in lower waste management emissions, the study says.

Prof Ke Yin, a professor at Nanjing Forestry University in China and one of the corresponding authors on the study, says that the team hopes that their findings will make people aware of the “huge amount” of food waste emissions. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Some countries have done some work to prevent food wasting, such as public education and government policies. Some examples are waste sorting in Japan, Germany and, more recently, China. Yet, many countries spend little to no effort [combating the problem] due to various reasons, such as poverty, inequality and political instability.”

Developing countries, in particular, face problems avoiding food waste after harvest. If producers, especially those in warmer climates, do not have access to refrigeration, the food can spoil on its way to the consumer.

The study uses food supply data from the FAO that covers 164 countries and regions between 2001 and 2017. It examines the loss and waste of 54 different food commodities across four different categories: cereals and pulses; meats and animal products; roots and oil crops; and fruits and vegetables.

The study assesses the waste emissions from different supply-chain activities and waste-management processes – taking a “cradle-to-grave” approach.

It examines emissions from food loss and waste created during nine different steps after the food is harvested and it travels along the supply chain. These supply stages are: harvest, producer, storage, transport, trade, processing, wholesale, retail and consumer use.

Researchers also assess the emissions resulting from food ending up in landfill or dump sites, examining how food loss and waste emissions vary depending on the country, region and type of food. Income, technological capacity and dietary patterns all affect emissions levels in individual countries and regional areas.

The study finds that – combined – China, India, the US and Brazil generate just over 44% of the global supply-related emissions from food waste and 38% of the global waste-management-related emissions.

The researchers say their findings could help decision-makers tailor different interventions on food loss and waste to specific local contexts.

Dr Melissa Pflugh Prescott, an assistant professor of food science and nutrition at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, who was not involved in the study, says that this localised aspect is an “important” component of the new study, adding that “the efficacy of solutions will differ depending on local contexts”.

Cutting down emissions

The researchers considered a range of intervention strategies to reduce food waste emissions, including halving food loss and waste generation, halving meat consumption and two different scenarios of the deployment of technological advances.

If food loss and waste were halved, the researchers find, this would remove around one-quarter of total greenhouse gas emissions from the global food system.

The charts below show the supply waste emissions from different food categories (left) and the percentage of food waste coming from different food types in various parts of the world (right).

Just 2.4% of global supply emissions from food waste come from fruits and vegetables, the study finds.

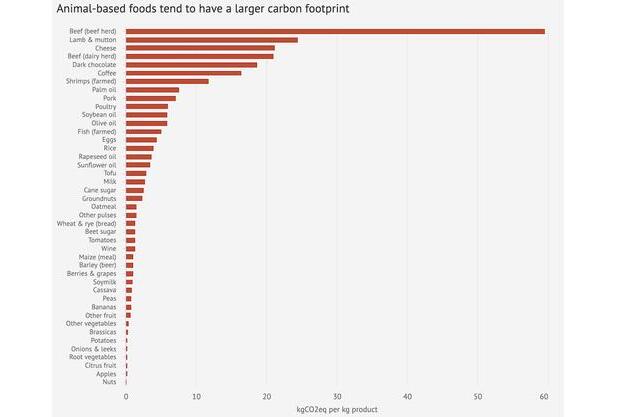

Meat and animal products result in higher emissions than other types of food. The new study highlights that the processing of beef and lamb generates 13 times more emissions than processing tomatoes in the overall production process.

Therefore, the study says, halving meat and animal product consumption would “profoundly lower the average dietary carbon footprint”, reducing overall food system emissions.

In this scenario, the calories of the meat and animal products are assumed to be replaced by the calories of the other three food categories in the study.

The researchers find that this would lead to an emissions reduction of 4.27GtCO2e from the global food system – comparable to that of halving food loss and waste generation.

But this comes at a cost. Reducing animal product consumption would lead to an increase in waste management emissions, as doing so would require increasing the production, consumption and wastage of cereals to compensate for the reduced meat intake, the researchers say.

Cereals and pulses account for between half and three-quarters of all waste-management emissions. This is due to their high carbohydrate content, which generates high emissions in many treatment processes, the study says.

Prescott says that this consideration of the trade-offs is “another strength of the study”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“This is very important as improvement in one aspect of the food system, such as consumer food use, may yield unintended consequences in other areas, such as waste management.”

Combining these two interventions – halving meat consumption and halving food loss and waste generation – would result in a 43% reduction in global food waste emissions, the study finds.

Using technology

The study also considers the effects of reducing landfill use and using existing technologies, such as anaerobic digestion and composting, to deal with waste.

Anaerobic digestion takes place in a sealed environment and uses bacteria to break down organic matter in the absence of oxygen.

Composting, on the other hand, needs oxygen to convert organic matter into mulch.

Currently, food waste is most commonly disposed of in landfills or dump sites, where it rots and produces methane. Composting and anaerobic digestion are both “promising alternatives” that can help reduce emissions from waste, the researchers write.

The researchers recommend that developed countries focus on improving logistics to reduce the generation of food waste and to improve waste management through composting and anaerobic digestion.

In developing countries, where improved technology may not be available as quickly, the researchers say that interventions should focus on actions such as long-term planning of waste-management facility upgrades.

Meat and animal products account for almost three-quarters of the supply emissions assessed by the researchers.

Beef, lamb and mutton have significantly higher emissions levels than other food groups, according to the chart below from a previous Carbon Brief article examining the climate impact of meat and dairy.

The new study says that areas with higher meat consumption, such as North America and Europe, have larger proportions of their supply emissions resulting from meat waste – upwards of 85%.

For populations that consume a lot of cereals and pulses, researchers say that there may be advantages if the emissions from waste management can be collected and used in other ways. For example, other researchers have assessed the potential of turning food waste from landfill into natural gas through anaerobic digestion.

Consumer choices

Emissions from food that goes to waste after people buy it from shops contributes to more than one-third of the total food loss and waste emissions on the supply side, according to the study.

The researchers find that a one-third reduction in emissions from China and the US at the consumer stage would be comparable to eliminating all global emissions generated from the processing and transport stages.

The study suggests advocating for “rational” food consumption behaviours and advancing technologies to reduce food loss and waste at the consumer level.

As of November 2022, 21 countries have committed to reducing food loss and waste in their national climate pledges under the Paris Agreement.

Prescott says it is “encouraging” that large countries such as the US are focusing more on reducing food waste (pdf), but adds that “there is more that needs to be done”.

She tells Carbon Brief that “more resources and priority should be placed on changing consumer behaviour” to avoid waste.

In some places, countries and local governments are undertaking different measures to tackle food waste.

For example, in 2016, France banned shops from throwing away unsold food, instead requiring them to donate to charities and food banks. China’s national legislature passed an anti-food waste law in 2021, setting out rules for public entities and private food and catering providers to improve food sourcing, management and preparation. And in South Korea, the vast majority of food waste is recycled and used to create biogas, bio oil and fertiliser.

The authors of the new study also suggest that “carbon labelling” on food products to show the environmental impact of the food could help reduce loss and waste.

Prescott says that carbon labelling “may help bring awareness to the issue”, but adds that it is “unlikely that carbon labelling or other educational interventions alone will make large reductions” in food loss and waste.